A major federal investment in public housing could tackle several urgent needs at once, from Covid stimulus to climate change, say progressive advocates.

By Kriston Capps, Bloomberg News

December 8, 2020, 12:09 PM EST

The Biden administration will have a narrow window in 2021 to set their agenda, and a long list of competing needs: Beyond the raging pandemic and the climate crisis, the new president will confront an ailing economy, steep racial and income inequality, and a potentially cataclysmic wave of housing instability. Some progressive advocates say that President-elect Joe Biden could tackle all of those at once by embracing a long-neglected national infrastructural need — public housing — as the engine for the recovery.

That’s the argument put forward by the Justice Collaborative Institute, a progressive nonprofit, in a new report to promote housing as a human right as well as a tool for achieving a variety of liberal wish-list items.

The report argues for building 12 million public housing units by 2030 and retrofitting the country’s current stock to be carbon neutral. The construction drive would generate more than 1 million jobs per year, according to the Justice Collaborative Institute, while the energy retrofits alone would create hundreds of thousands of additional jobs — critical at a time when pandemic-driven adoption of new technologies is threatening to speed job loss. “Algorithms still can’t build houses. Robots still can’t build houses,” Cohen says. “It takes people.”

The toolkit is nothing new, either: The federal government already subsidizes homeownership to the tune of tens of billions of dollars through the mortgage interest tax deduction, to name just one of the federal programs that has helped the white middle class build wealth over the last century.

And the housing situation could be much worse in 2021 for millions of vulnerable families, depending on whether federal authorities take action to replenish emergency assistance and extend the federal eviction moratorium. As many as 19 million households could face eviction in the New Year if the current moratorium expires at the end of December.

Despite the profound need, skeptics of the idea may point to the last time the federal government embarked on a social housing initiative: Many postwar public housing projects in U.S. cities became iconic symbols of poverty and crime as a result of federal neglect. The shadows of Pruitt-Igoe and Cabrini Green loom over any discussion of public housing in the United States. But Cohen and co-author Mark Paul, assistant professor of economics and environmental studies at New College of Florida, argue that the notorious failures of the projects of the 1960s and ’70s were doomed by design, a product of systemic racial disparities and disinvestment that turned housing projects into communities of concentrated poverty. It could have gone differently: A broad plan under the New Deal to build better social housing was amended, revised and ultimately undermined before it had a chance. The nation’s safety net might have included a guarantee of safe housing for every resident, a promise like Social Security or Medicaid.

Other nations manage to make it work. Cohen and Paul point to the Vienna model for social housing, where more than 60% of the population in the Austrian capital lives in some 440,000 housing units owned by either the city government or state-subsidized nonprofits. It’s not an easy task, as the U.K.’s struggle to maintain its public housing stock shows, especially in light of the deadly Grenfell Tower fire. But a renewed federal housing program could avoid repeating previous mistakes by following the fair housing laws established during the Civil Rights era and by reversing the decades-long project to defund the safety net.

More to the point, the status quo today is nothing to brag about. Current federal efforts to entice the market to solve the housing problem — including insufficient Section 8 vouchers and byzantine housing tax credits — have done little to satisfy the nation’s need for safe, affordable, equitable housing, the report argues. “We have millions of Americans who are currently homeless. We have more structures than we have families,” Paul says. “We need to set up a reasonable floor for the housing market.”

Done right, social housing could help to ease the climate crisis by building energy-efficient homes that generate green jobs. Locating these homes near public transit would also ease or at least not worsen the environmental cost of sprawl. (It could also speed the recovery of transit systems that are currently fighting for their lives amid Covid-fueled ridership drops.) Building new public housing (and retrofitting existing public housing) in cities could help to prevent or reverse displacement in neighborhoods that have grown prohibitively expensive. Social housing has a role in rural areas, too, where the aging housing stock is putting a strain on seniors especially. With interest rates at historic lows — and rents cratering in cities due to the pandemic — the timing is ideal for a large-scale public mobilization.

For the first time in a generation, policymakers are looking at public housing as a political possibility. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced a Green New Deal for Public Housing Act that would commit $180 billion over a decade to upgrading and climatizing the nation’s public housing stock. Their bill would repeal the Faircloth Amendment, which has effectively banned new federal public housing since 1999. Minnesota Representative Ilhan Omar’s proposed Homes for All Act goes further, by committing $1 trillion to the construction of some 9.5 million new public housing units.

Before the pandemic, Omar’s bill arguably served as an aggressive mile-marker for the progressive agenda; after the economic devastation of Covid-19, a trillion-dollar housing push might be a right-sized effort to save the economy.

It’s not just the Squad taking up the housing agenda. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi copied-and-pasted much of the language on housing in the proposed HEROES Act from California Representative Maxine Waters’s Housing Is Infrastructure Act. President-elect Joe Biden has pledged to build at least 1.5 million affordable and sustainable homes. While social housing doesn’t appear on Biden’s housing platform, the Justice Collaborative Institute report authors argue that his commitments would work hand-in-glove with a public option.

“The most important piece of Biden’s platform from our perspective is the promise that 40% of the benefit of $2 trillion in green stimulus would go to disadvantaged communities,” Cohen says. “There is no doubt that there is a lack of high-quality, healthy, affordable housing in disadvantaged communities.”

Activists have worked for years to lay the groundwork for these efforts from progressive lawmakers. Tenant advocates are not content to fiddle with the percentages on Low Income Housing Tax Credits in hopes of incentivizing change. People’s Action, a national grassroots network, developed a framework in 2019 called the Homes Guarantee to build 12 million social housing units. Candidates for local and statewide offices in at least 8 states committed to the pledge in the run-up to the 2020 election. Tara Raghuveer, the founding director of KC Tenants and housing campaign director for People’s Action, told me at the time that the Homes Guarantee was part of a broader mobilization to decommodify housing.

“Incrementalism is dead when it comes to housing,” Raghuveer says. “We need a complete overhaul.”

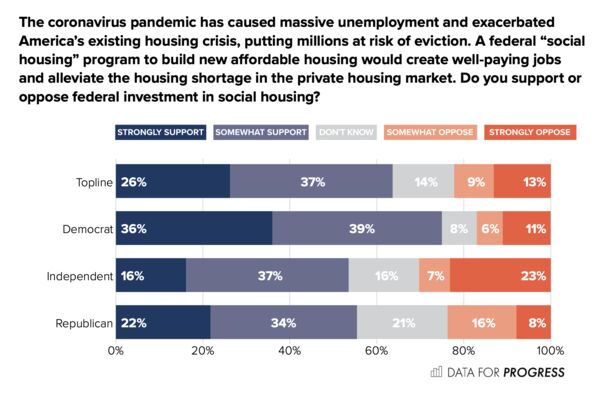

Social housing supporters say that the public is on their side. A recent poll conducted by the Justice Collaborative Institute and the left-leaning policy shop Data for Progress finds that 63% of likely voters support federal investment in social housing. (The poll asked about social housing specifically, not public housing, a better-known term in the U.S.) Some 56% of Republicans said they would support social housing (along with nearly 80% of Democrats).

Public perception of the issue might change, of course, if and when the conservative opposition puts it through the meat grinder. After all, President Donald Trump built a months-long scare campaign around Democratic efforts to enforce fair housing rules, claiming that Biden was determined to “abolish the suburbs” by encouraging low-income housing in affluent areas. Suburban voters weren’t convinced, however. Now progressives are saying, basically, that Biden should do exactly what Trump feared — build inclusive, accessible, subsidized homes in communities across the country.

One rule for a Biden social housing agenda: Don’t build bleak. European leaders are on this tip, too, with a massive building energy retrofit campaign that they’re comparing to a second Bauhaus. Done right, and at a scale sized to solve the problems at hand, public housing in the U.S. could manifest speedily as good government in action. (Something that critics say was missing in the shovel-ready projects of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.) Public housing could be a priority among “unsexy infrastructure” — the grab-bag solution for stimulus spending on roads, rails, broadband and so on — since it has much more profound and immediate consequences for millions of people who will find themselves without homes in 2021.

The next few weeks will shape the prospect for social housing in profound ways. Democrats have a chance to win the Senate in the January run-off elections in Georgia. If they succeed, the party’s lawmakers will be able to pass legislation through budget reconciliation, which requires only a simple majority in the Senate. A massive legislative investment in housing would need the support of moderates such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, so it’s a long shot, to say the least. But it’s at least a possibility under budget reconciliation.

In the short term, building out the social safety net can help to repair a damaged economy, promote new green technologies and reorient the country away from sprawl. The long-term promise of social housing is that Americans won’t ever have to face catastrophic rent burdens, unsafe homes or sleeping on the streets. That’s a moon shot the U.S. could reach within a decade.

“Homeownership should not be the only goal,” Paul says. “What we’re proposing is quite reasonable.”